Nathan Lopes Cardozo

This article will appear in the Hebrew Makor Rishon

Erev Rosh Hashana, 5772

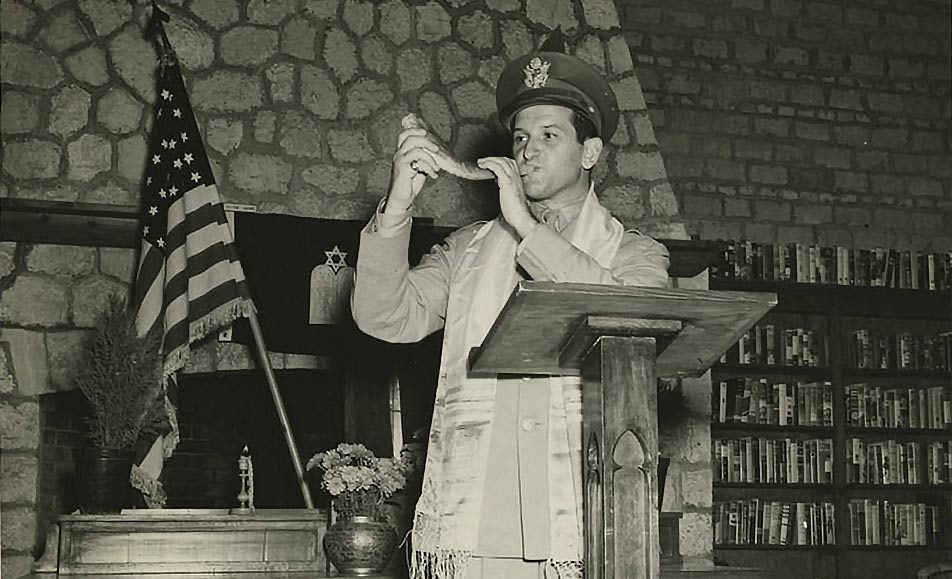

Rosh Hashana is a day to contemplate the need for great Jewish Ideas. A day to think big. To get out of our compartmentalized boxes. Hayom Harat Olam: Today the world is born. On Rosh Hashana the world should be newly created. This is specifically important for the future of Judaism.

Most religious Jews are not aware that Judaism has become passé. They believe that Judaism is doing great. After all, we have more learning, more Jewish schools, more yeshivot, women’s seminaries, outreach programs and books on Judaism than ever before. Despite this, Judaism suffers from a major malady. In truth, it is not only Judaism that suffers from this disease, but the whole world. We lack great bold ideas. We have fallen in love with—and become overwhelmed by—an endless supply of all-encompassing but passive information, which does not get processed but only recycled. We can access trillions and trillions of sound bites in the ether which expose us to every kind of information, providing us with all the knowledge we could ever dream of. The problem is that this easily accessible information has replaced creative thinking. It has expelled the possibility for big ideas; we have grown scared of them. We only tolerate and admire bold ideas when they provide us with profit-making inventions. When we feel our empty pockets, but not when they dare challenge our empty souls. We do not discuss big ideas because they are too abstract and too airy. Novelty is always seen as a threat. The new always carries with it a sense of violation; a kind of sacrilege. It asks us to think, to stretch our brains—which demands too much of an effort and does not suit our most important concern: The need for instant satisfaction. We love the commonplace instead of the visionary and therefore we do not produce people who have the capacity to deliver true innovation.

It is only among some very small secular elite groups that we see some staggering ideas emerging (Hawking and quantum theory, Aumann and game theory); in the department of Judaism, we rarely find anyone who even gets close to suggesting something new. This is all the more true within “Orthodox” Judaism. While in ages past, discussions within Judaism could ignite fires of debate, incite revolutions and fundamentally change our views about Judaism and the world, as when the Baal Shem Tov created Chasidism, we are now confronted with an increasingly post- idea Judaism. Provoking ideas which would stagger our minds are no longer “in.” If anything they are condemned as heresy. Since they can’t easily be absorbed into our self-made religious boxes, and do not bring us the complacency we long for, we stick to the mainstream where we can dream our mediocre dreams and leave things as they are.

Most of our yeshivot have retreated from creative thinking. We encourage the narrowest specialization rather than push for daring ideas. We are producing a generation which believes that its task is to tend potted plants rather than plant forests. We offer our young people prepared experiences in which we tell them what to think instead of teaching them how to think. We rob them of the capacity to learn what thinking is really all about. The onslaught of halachic works which educate them in the minutiae of the most intricate parts of Jewish law hardly generate inspiring or new ideas about these laws. In fact, they stand in the way. There is no time to process all the information even if they want to. But instead of seeing that this is a problem, they and their teachers have turned it into a virtue.

And that is exactly my point. We are faced either with our youth walking out on Judaism or maintaining a lukewarm relationship with Jewish observance, or at the other extreme, some get so obsessed by its finest points that they become incapable of seeing the forest for the trees, and consequently turn into rigid religious extremists.

What we fail to realize is that this is the result of our own educational system. In both cases, young people have fallen victim to the disease of information for the sake of information.

Information is not simply to have. Real information is there to be converted into something much larger than itself. It is there to produce ideas which make sense of the information gathered and can move it forward to higher latitudes. Information is not there to be apprehended, but to be comprehended.

Jewish education today is, for the most part, producing a generation of religious Jews who know more and more about Jewish observance but think less and less about what they know. This is even truer of their teachers. Many of them are great Talmudic scholars, but these very scholars do not realize that they have drowned in their vast knowledge. The more they know, the less they understand. Just like a bird may think that it is an act of kindness to lift a fish into the air, so these rabbis may be choking their students while thinking that they are providing them with spiritual oxygen. Doing so, they rewrite Judaism in ways that are totally foreign to the very ideas that Judaism truly stands for. They are embalming Judaism while claiming it is alive because it continues to maintain its external shape.

Less and less young religious people have proper knowledge of the great Jewish thinkers of the past and the present. And even when they do, the ideas of these great thinkers are presented to them as information instead of as challenges to their own thinking or as prompts to the development of their own creativity. This is a mistake. Our current spiritual and intellectual challenges cannot be answered by simply looking backwards and giving answers which once worked but are now outdated.

Instead of new theories, hypotheses and great ideas we get “instant” answers to questions of the greatest importance, offered via all sorts of “self help” books which seem to claim that their philosophical information came directly from Sinai itself. Trivial, simplistic, and often incorrect information pushes out significant ideas. The information is merely “tweeted”—and is thus too brief and unsupported by proper arguments —but nevertheless is presented as the “answer.” By delivering “perfect” answers which fit nicely into the often underdeveloped philosophies of their authors, everything is done to crush questioning. The quest for certainty paralyses the search for meaning. It is uncertainty that is the very condition that impels man to unfold his intellectual capacity. Every idea within Judaism is multifaceted, filled with contradictions, opposing opinions, and unsolvable paradoxes. The greatness of the sages of the Talmud was that they shared with their students their own struggles and doubts, and how they tried to solve them, as when Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai debated the essential, existential question of whether man should have been created at all (Eruvin 13b). Teachers made students privy to their own inner lives. In that way they made their discussions exciting. They created tension in their classes, waged war with their own ideas and asked their students to fight with them with knives between their teeth. They were not interested in teaching their students dogmas, but instead asked them to take them apart, to deconstruct them so as to rediscover the questions. These teachers realized that not all paradoxes can be solved, because life itself is full of paradoxes. They also realized that every answer is always a form of death—but a question opens the mind and inspires the heart.

It is true that this approach is not without risk, but there is no authentic life choice that is risk free. Nothing is worse than giving in to the indolence and callousness that stifles inquiry and leaves one drifting with the current. Such an approach shrinks Judaism’s universe to a self-centered and self-satisfying ideological ghetto, robbing it of its most essential component: The constant debate about the religious meaning of life and how to live in God’s presence and move to higher levels.

Outreach programs, although well intended, have become institutions which, like factories, focus on mass production and believe that the more people they can draw into Jewish observance, the more successful they are. That their methods crush the minds of many newcomers who might have made a major contribution to a new and vigorous Judaism is of no importance to them. The goal is to fit them into the existing system. That their outdated theories make other independent minds abhor Judaism is a thought they do not seem to contemplate. To them, only numbers count. How many people did we make observant? Millions of dollars are spent to create more and more of the same kind of standard religious Jew. Not unlike in the generation of the Tower of Babel, in which the whole world was of “one language and of one speech,” so we are producing a religious Jewish community of artificial conformism in which independent thought and difference of opinion is not only condemned, but its absence is considered to be the ultimate ideal. We have created a generation of yes men. We desperately need to heed what Kierkegaard said about Christianity: “The greatest proof of Christianity’s decay is the prodigiously large numbers of (like-minded) Christians” (see M.M. Thulstrup’s “Kierkegaard’s Dialectic of Imitation” in A Kierkegaard Critique, H Johnson and N Thulstrup, eds., NY 1962).

Insight has been replaced with clichés, flexibility with obstinacy, spontaneity with habit. What was once one of the great pillars of Judaism, the great value of spiritual, intellectual and moral dissent, has become anathema. Instead of teaching the art of audacity we are now educating a generation of kowtowers. There is social ostracism of any kind of healthy rebellion against the conventional—Eliezer Berkovits was ignored when he argued that halakha had become only defensive; the master thinker Abraham Joshua Heschel is completely disregarded by orthodoxy; Chareidi yeshivot pay no attention to Rav Kook. Above all, we see dishonest attempts to portray fundamentalism as a genuinely open-minded intellectual position while in truth it is nothing of the sort. Great visions of the past are misused and abused. Today we are seeing many people being told that they must imitate so as to belong to the religious camp. Spiritual plagiarism has been adopted as the appropriate way of religious life and thought.

It is true that there are still dissenters in Judaism today—and they are growing in number. There are even some yeshivot and institutions which dissent, such as Yeshivat Otniel, Yeshivat Siach Yitzchak and our own Beth Midrash of Avraham Avinu of the Cardozo Academy. But the great tragedy is that these places speak in a small voice which the religious establishment is unable to hear. Instead, the establishment puts its weight behind the insipid and the trivial, and has fallen in love with the uncompromised flatness of mainstream institutions which “deliver” by large numbers and offer instant answers to people who find themselves in religious crisis.

Original Jewish thinkers today—Tamar Ross, Yehuda Gellman, Susan Handelman, Michael Wyschogrod—fall victim to the glut of conformists. While these thinkers challenge conventional thinking, they remain unsupported and live lonely lives because our culture writes them off. It serves only the idol worship of intellectual and spiritual submission rather than saying yes to new religious ideas which we are in desperate need of.

In fairness, it is not much different in the non-Jewish world. Were Socrates, Plato, Kant or Spinoza alive today, they would barely be mentioned in the media other than in some specialized philosophical journals which nobody reads. What our generation does not understand is that without these giants of the past we would still be living in a primitive world in which science would not have given us all the knowledge and luxuries which we enjoy today. Because it was these thinkers, whether we agree or disagree with them, who produced the great ideas which laid the foundations of much of what we have harvested through the centuries. Today they would be crowded out by massive quantities of trite sound bites that only lead to self-satisfaction.

And so it is with Judaism. Most Talmudic scholars do not realize that the authors whose opinions they teach would turn in their graves if they knew that their opinions were being taught as dogmas which can’t be challenged. They wanted their ideas tested, discussed, thought through, reformulated and even rejected, with the understanding that no final conclusions have ever been reached, could be reached or should be reached. They realized that matters of faith should remain fluid, not static. Halacha is the practical upshot of un-finalized beliefs while remaining in theological suspense. Only in this way can Judaism not become a religion that is paralyzed in its awe of a rigid tradition or evaporates into a utopian reverie.

The parents who today are worried by their children’s lack of enthusiasm for Judaism do not realize that they themselves support a system which systematically makes such passion impossible.

What today’s Judaism is desperately in need of is great critics who could fructify and energize its great message. It needs spiritual Einsteins, Freuds and Pasteurs who could show its untapped possibilities and still undeveloped grandeur. Judaism should be challenged by new Spinozas and Nietzsches; by remorseless atheists who would scare the hell out of our rabbis who would then be forced into thinking bold ideas.

The time has come to deal with the real issues and not hide behind excuses which ultimately will turn Judaism into a sham. Our thinking is behind the times, and that is something that we can no longer afford. This is the great challenge with which Rosh Hashana confronts us. Judaism is about bold ideas. Its goal is not to find the truth, but to inspire us to honestly search for it. Torah study is not only the greatest undertaking there is, but also the most dangerous, since it can so easily lead to self-satisfaction and spiritual conceit. The leashing of our souls is easier than the building of our spirit.

What we need to do is to search for Judaism in its embryonic form, before it was solidified into the halacha as we know it today. To return to its great ideas with its many opinions and to develop them in ways which can answer the many different spiritual needs of modern man and inspire his soul.

We need to be like Rembrandt, the great Dutch painter, who unlike all the other painters of his generation, used the raw material of the landscape of Holland to perceive hidden connections—linking his preternatural sensibility to a reality that he was able to transform, with great passion, into a new creation. He found himself in a state of permanent antagonism to his society, and yet he spoke to his generation and continues to speak to us because he elevated himself to the point where he was able to see the full dimensions that art could address and yet nobody else had discovered. Just like art, one can’t inherit faith and one can’t receive the Jewish tradition. One must earn and fight for it. To be religious is to live in a state of warfare. The purpose of art is to disturb; not to produce finished works but to stop in exhaustion in the middle for others to continue. So it is with Judaism. It still has scaffolding, and the scaffolding should remain while the building continues.

We are not advocating revisionist reform-like positions just for the sake of being novel. History has shown that such approaches do not work and they often lack the genuine religious experience. We should not be overanxious to encourage innovation in cases of doubtful improvement; a brand-new mediocrity should not replace well-established excellence. One does not discover new lands by losing sight of the shore from where one began one’s journey. But the time has come to rethink Jewish education as it is taught in many traditional places. We are in need of a radically different kind of yeshiva. One in which students are challenged about their beliefs, where they are confronted with Jewish and non-Jewish thinkers’ critiques on Judaism and learn how to respond. Where they become aware that it is not certainty, but doubt, which gets you an education. Where it is not rabbinic authority which reigns supreme, but religious authenticity. A yeshiva where the teachers have the courage to share their doubts with their students and show them that Judaism teaches us how to live with uncertainty and through that uncertainty to be deeply religious people. Students need to learn that just as in life, Judaism is the art of drawing sufficient conclusions from insufficient premises. A reasonable probability is the only certainty we can have.

There is an urgent need to set up “Tents of Avraham” throughout the land of Israel, where religious and non-religious Jews can study, discuss and argue the great faith positions of earlier and later generations. To engage in the wonder of Judaism, to study its own struggles, its worries, and its constant search for new understandings of itself. Where there can be honest discussions, even if it turns out that some components which are now seen as fundamental to Judaism may need to be replaced. The need to break idols and to take down sacred cows is itself a Jewish task which Avraham himself initiated. No doubt there will be fierce arguments, but we should never forget that great controversies are also great emancipators.

Broad change is not just window dressing, and it can be painful. It is liberating and refreshing, but it comes with a cost—but without it there is not only no future for Judaism, but no purpose.

May the good Lord bless us with bold ideas which will put His Torah into the center of our lives and make us receptive to His presence through a daring new encounter with Him. Let it be heroic. Not staid and comfortable, but painful and hard-won. A deep breath in the midst of the ongoing conflict present in the heart of humankind.

Share This Post