There is an argument known as the Kuzari Principle. It tries to justify belief in whole swathes of the Biblical narrative, especially in the revelation at Mount Sinai. In this blog post, I hope to show that the argument is much stronger than it might seem. The name of the argument is slightly unfair, as it was first put forward not in R. Yehuda Halevi’s Kuzari, but in Saadya Gaon’s Emunot Vadeot.

Saadya Gaon starts out by noting that of all the public miracles witnessed by the Jewish people, he ‘personally … consider[s]the case of the miracle of the manna as the most amazing … because a phenomenon of an enduring nature excites greater wonderment than one of a passing character.’ He goes on to consider how the Jewish people could ever have come to believe that such a thing occurred:

Now it is not likely that the forbears of the children of Israel should have been in agreement upon this matter if they had considered it a lie… Besides, if they had told their children: ‘We lived in the wilderness for forty years eating nought except manna,’ and there had been no basis for that in fact, their children would have answered them: ‘Now you are telling us a lie. Thou, so and so, is not this thy field, and thou, so and so, is not this thy garden from which you have always derived your sustenance?’ This is, then, something that the children would not have accepted by any manner of means.

The Khazari King with whom the Rabbi debates, in the Kuzari, wants to know why the Rabbi introduced his God as ‘The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,’ instead of by the more grand description, the creator of the heavens and the earth.The Rabbi states that he was following a hallowed precedent: ‘In the same strain spoke Moses to Pharaoh, when he told him: ‘The God of the Hebrews sent me to thee,’ viz. the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob … He did not say: ‘The God of heaven and earth,’ nor ‘my Creator and thine sent me.’ In the same way God commenced His speech to the assembled people of Israel: ‘I am the God whom you worship, who has led you out of the land of Egypt,’ but He did not say: ‘I am the Creator of the world and your Creator.’’ And the reason that the Rabbi gives for this traditional façon de parle is that the Jewish relationship with God is, first and foremost, a personal one. They have known God directly through His miracles and providence, and thus, ‘I answered thee as was fitting, and is fitting for the whole of Israel who knew these things, first from personal experience [especially via the national revelation at Sinai], and afterwards through uninterrupted tradition, which is equal to the former.’

What we call the Kuzari Principle is what I italicized in the quotation: Personal experience is equal to uninterrupted tradition as a ground for belief. Surely the principle is in need of some refinement, but the basic idea is true. The scientific community doesn’t feel the need to repeat every experiment ever conducted before accepting the relevant findings for themselves. If there wasn’t a modicum of trust given to the testimony of past scientists about their findings, then we could never move on, because we’d first of all have to repeat the entire history of science in our own laboratories. If we take the best elements of these medieval arguments and try to fashion them into something formal, and prima facie worth considering, we end up with something like the following:

(KP1) If a reliable witness, called person-y, witnesses an event, event-x, and an uninterrupted chain of reliable sources passes on person-y’s testimony, even over many years, then, given certain provisos about the make-up of the chain, about person-y and about the reported circumstances of the original observation, we have good reason to believe that event-x transpired.

(KP2) The epistemic warrant provided by such a chain increases with the number of reliable observers in the chain who claim to have witnessed the event themselves.

(KP3) The Biblical Narrative states that the entire Jewish nation witnessed the revelation at Mount Sinai and the miracles of the exodus.

(KP4) The Biblical and Jewish Narrative, as well as Jewish History, indicate that every generation of Jews after the exodus and the national revelation passed the story on to their children. This chain continues until this day.

(KP5) Jewish children in every generation, given1 and 2, have good grounds for believing that there really was a miraculous exodus and a national revelation.

The argument can also be put in the following terms:

(KP*1) For any widespread historical belief, the belief is either true, or was sold to the general public via some sort of witting or unwitting deception.

(KP*2) The historical belief in the national revelation at Sinai is widespread among the Jewish people, as is the belief that this knowledge has been passed down faithfully from generation to generation since the event itself.

(KP*3) Given (KP*1) and (KP*2), the Jewish belief in the revelation at Sinai is either true, or was sold to them via some sort of deception.

(KP*4) At no point in time could a whole nation have been deceived into the content of the story in question. A nation could certainly be deceived about ancient history, as many Britons were deceived into believing that there was a King Arthur in a court called Camelot. But part of the story that we’re talking about, as specified in (KP*2), makes the outlandish claim that every generation,including the generation that is now listening to the story, received the tradition from their parents. Thus the Jewish people would never have adopted the narrative in question, unless all of their parents had already told them the story. At no point would the Jewish nation have bought the lie that millions of their forbears witnessed something and that it was faithfully passed down from generation to generation, unless all, or most of the parents of their generation had already told them, and unless the nation was already a sizeable nation.

(KP*5) Given (KP*4), the widespread belief among the Jewish people in the story of the revelation couldn’t have been spread by deception.

(KP*6) Given (KP*5) and (KP*1), the widespread belief among the Jewish people in the story of the revelation must be true. The same argument will work for the story of the exodus from Egypt.

If this argument is sound, then the Jewish people have good reason to believe that there really was a miraculous escape from Egypt and a revelation at Mount Sinai.

Unfortunately, the arguments which the medieval philosophers used in order to grant Judaism its Divine sanction are open to various criticisms. I think that they can be overcome, if we’re willing to revise the argument somewhat, but first, I list the criticisms.

(P1) Both of the arguments above only get going if we assume that the Jewish people were relating to their narratives as a history. But I often argue on this blog that the Biblical narratives are wrongly regarded as an attempt at history;that they have more in common with myth.

(P2) We all know that traditions handed down from generation to generation are subject to corruption. The scientific community only trust their forbears to the extent that they had rigorous methods for observing, recording, and transmitting their results. This cannot be said of an ancient society. So, even if the argument can prove that something remarkable happened to an entire nation in the desert,we have no reason to trust any of the details of the story.

(P3) Building on from (P2): It is generally taken for granted, among archaeologists and Biblical critics, for instance, that the ancient Jewish religion grew up slowly as different tribes with different religious traditions and narratives merged.As those tribes merged, the narratives merged. Thus the narratives in question are more likely to have been the product of a slow evolution than to have been the product of a reliable chain of testimony over time.

(P4) In the book of Kings II, chapters 22-3, it is reported that a hitherto unheard of scroll was found in the temple. Many scholars think that the scroll’s appearance marks the moment that the book of Deuteronomy was first introduced to the Jewish people. The story implies that everybody accepted, uncritically,that the scroll and its content were authentic. Nobody asked how there could have been an ancient, God given, book of the Bible that nobody had told them about beforehand. This all implies that people were more susceptible to deception than (KP*4) allows for.

(P5) The Bible and the prophets don’t try to hide the fact that at various points throughout Jewish history, idol worship was widespread, and that there was a need to encourage a return to Judaism. So a story about a mass revelation that was subsequently forgotten might have been easy to spread at some points in time precisely because idol worship had taken over for generations, and thus nobody would have been surprised that their idolatrous parents hadn’t told them.

I will respond to these criticisms in turn, and in so doing, a new and improved version of the argument will hopefully arise.

In response to (P1), I say the following. I still maintain that when faced with a narrative about his distant history, the ancient Israelite was unlikely to have been concerned, at least first and foremost, with the story’s historical accuracy rather than with its ethical force, symbolic resonance, and personal impact. This wasn’t because they had no notion of truth and falsehood. On the contrary, they must have had. Rather,they wouldn’t have worried about historical accuracy for two reasons: 1) the narratives were to be related to, culturally, as myth rather than history, and 2) the narratives in question concerned the distant past; since they didn’t have any of the tools that we now have, from archaeology to cosmology, to verify the historical claims of narrative about the distant past, they simply had to abandon the desire for historical accuracy – there was no way of knowing either way. But, some of the stories of the Bible, especially those from the exodus and onwards, wouldn’t have struck, and still don’t strike the Jewish reader purely as being about the ancient past,lying beyond the verificataroy reach of a primitive people; some of those stories don’t just posit that some events occurred a long time ago; they also posit an uninterrupted chain of transmission from then until now. I want to call that kind of story a g-narrative. G-narratives are any story with the following two characteristics:

(G1) The events of the story were, according to the story itself, witnessed by an entire generation of an already numerous tribe/nation.

(G2) The story itself claims that the witnesses endeavored to initiate a chain of transmission from generation to generation – ‘And you shall tell your child’ –such that their progeny would never forget what they saw.

Jewish narratives are treated, by the religion, as myth – given that it bases rituals, retellings and re-livings upon them. But, myths can be based upon historical facts. The truth or falsehood, in terms of historical accuracy, of a myth is not a key factor in the worth of that myth. But, when some of the historical claims of a myth do lie within the verificatory grasp of a culture, that myth is unlikely to be adopted, unless its historical claims were seen to have stood up. Once a myth is adopted, however, and embedded into a religious culture, like the myth of the Garden of Eden, for example, its historical accuracy is no longer relevant to its worth as a religious myth.

G-narratives,even when their story lines are set a long time ago, are not completely beyond the verificatory reach of their audience, because, at the very least, the audience will know whether the story was passed down to them by the entirety of the previous generation. G-narratives in the body of Jewish narratives are an exception, rather than the norm. But they are significant for the following reason: it’s difficult to believe that any g-narrative could have become widespread as a myth unless it had been passed down from generation to generation. The only generation that would have accepted a g-narrative, even as the basis of a myth, or so it seems to me, would be the generation that witnessed the key events of the story for themselves. Otherwise, they’d have said, ‘I didn’t see this, and no one ever told me about it before now!’ If a g-narrative is widespread across a culture, however primitive, you’d have good reason to believe that its central story line, or something similar to it, actually occurred. To accept this thesis is not to revert to anything like an historiographical approach to Jewish narrative in general.

It’s also worth pointing out just how few of the central Jewish narratives a reg-narratives. All of the stories that pertain to times before the emergence of the Jewish people fall short of being g-narratives. All of the narratives that weren’t supposed to have happened before the entire nation also fall short.There are even narratives that talk of miracles that were beheld by the entire nation, such as the sun standing still for Joshua, that fail to be g-narratives because the story doesn’t talk of an endeavour to pass the story on from generation to generation. The story of the exodus from Egypt and the mass revelation at Mount Sinai, which are both accompanied with commandments to keep the story alive, are some of the rare occasions in which a Jewish narrative can claim to be a g-narrative. In fact, very few religious or historical narratives outside of Judaism can claim to be g-narratives either.

In response to (P2), I have to make some concessions. It’s true. A narrative transmitted down the generations can be subject to all manner of subtle and gradual evolutions. Imagine a massive inter generational game of Chinese Whispers. By the time that the message has reached the end of the line, its originator has died, and can’t tell you whether its integrity has been preserved. Nevertheless, one would imagine that the main headlines of the story, even if all of the details became perverted, would remain constant down the chain. Any major rupture or change to the general plot-line, and any diminution of its most striking claims, would surely be noted by a public in love with its legends and folklore. But, we can imagine a gradual process of exaggeration, and we can imagine a gradual corruption of mundane details. For that reason, a widespread g-narrative cannot be trusted as an accurate history. Its religious function, thankfully, isn’t to serve as an accurate history – because as I say, historical accuracy isn’t the purpose of myth. But, one can trust, or so it seems, that its main claims must have had some basis in fact, however tenuous. An uninterrupted chain of testimony doesn’t have the truth-preserving qualities attributed to it by Saadya Gaon and R. Yehuda Halevi, but it does justify the less ambitious claim that the story must have had some sort of grounding in fact. The story of the exodus and the revelation at Sinai is now a widespread g-narrative. This seems to justify the claim that an entire nation or tribe had some remarkable religious experiences,once upon a time, even if the finer details of the story can’t be trusted as an accurate historical account.

I don’t want to get into the whole question as to the reliability of Biblical criticism and the historical claims that are made in its wake. Inspired by Umberto Cassuto, I have my doubts about Biblical Criticism as a science. Notwithstanding, I think that the whole question is largely irrelevant to the philosophy of Judaism. Traditional Judaism relates to some of its texts as if they were written, word for word,by God Himself. The philosophically interesting question is: what does that attitude towards that text achieve;what effect does it have; why and how? Even though I’m dubious about the findings of Biblical Criticism, and dubious of their philosophical relevance even if they’re true, I would like to assume, only for the sake of argument,that the Biblical Critics are right about the way in which the Jewish people slowly grew into one nation via an amalgamation of different tribes; that each tribe brought with it its own variously divergent religious narratives and traditions. I contend that even if we accept this assumption, a version of the Kuzari Principle can still get through. This would show, in turn, that (P3) simply isn’t worth worrying about.

A tribe is unlikely to accept a g-narrative if they didn’t witness the events of the narrative for themselves, or if they didn’t inherent the narrative as a tradition from the previous generation. But, there is one important class of exceptions. At any point in the life of a tribe, outsiders can join that tribe.When they do, they often adopt the history of their new found tribe as their own. As a British Jew, I was taught British history, even by my parents, as if that history was my own, even when the historical events in question happened long before my ancestors became British. I have had conversations with American Jews in which they mock me and my kind for having lost the war of Independence against the Americans in 1777, but, in 1777 both their ancestors and mine were living in Eastern Europe! When outsiders join a tribe, they adopt its narrative as their own.

Let usimagine that tribe A has a g-narrative. Let us imagine further that members of tribe B or even the whole tribe joins tribe A. At that point, members of tribe B, who have joined tribe A, start to teach their children the g-narrative of tribe A as if it were their own history. It is still true to say that tribe Ais unlikely to have had a g-narrative in the first place unless they had witnessed its key events for themselves, or if they had inherited the narrative from the generation before them. Thus, it’s still true to say that the existence of the g-narrative is good grounds for believing that its content is in some way grounded in fact. Even if new members of the generational chain of transmission (henceforth, the g-chain) find their way into that chain somewhat artificially. Nothing in this example is changed when two tribes merge and decide to adopt one another’s narratives. When the narratives areg-narratives, their very existence, which allows them to play a role in the inter-tribal merger, is good evidence that their content is somehow grounded in fact.

Thus,even if the Jewish people and their narratives emerged after a long process of inter tribal merging, the presence of g-narratives in the resulting tradition is still good evidence that those narratives are grounded in fact. For that reason, it seems that (P3) is largely irrelevant to the Kuzari Principle.

In response to (P4): It is true that ‘a book of the Torah’ was discovered in the temple during the reign of King Josiah, according to Kings 2, chapters 22-3. Let us concede for the moment, that the book discovered was the book of Deuteronomy, or some forerunner to that book, as is the consensus among Bible scholars. It is interesting to note that the book of Deuteronomy, though it contains mentions of certain g-narratives, isn’t the source of any of them. The book of Deuteronomy is generally just a re-cap of the previous books of the Bible, of both their narrative and legal sections.

There are, admittedly, a few new laws in the book, but from the context of the story of its ‘rediscovery’ in the temple, we see that King Josiah was impressed not so much with new information, in terms of new stories or new laws. What impressed King Josiah about the book seems to have been, if it was the book of Deuteronomy, the stirring words of rebuke that Moses delivers in it to the Jewish people. Moses warns the Jewish people, in the book of Deuteronomy, that if they sin, and follow other Gods, as they were doing in the time of King Josiah, that there would be great suffering and destruction. It was this information, more than anything else in the book that seems to have moved King Josiah to tears, and to renting his clothes. When King Josiah declares: ‘[G]reat is the wrath of the LORD that is kindled against us, because our fathers have not hearkened unto the words of this book, to do according unto all that which is written concerning us,’ he sounds like a man who’s had the fear of God driven in to him by the fearful threats of Moses in the book of Deuteronomy.

The ‘discovery’ of this book of the Torah is irrelevant to the Kuzari principle fora couple of reasons. Firstly, if it was the book of Deuteronomy, then it doesn’t bear any relevance to Jewish g-narratives, as none of them originate in the book of Deuteronomy. Secondly, it seems that what the discovery of the book inculcated, consistent with it’s being the book of Deuteronomy, was a new found religious fervour rather than a new found religion!

In response to (P5) I make the following point: the Biblical account of Jewish history, consistent with everything we know about religiosity in the ancient near east, paints a picture of a people in which syncretism and monolatrism were generally rife. If this is the case, then just because belief in and worship of other gods may have waxed and waned, there is no reason to think that knowledge of, and belief in the God of the Hebrew Bible, and the associated g-narratives ever disappeared. Instead, the God of the Hebrew Bible was often regarded, by the Jews of the Bible, as one of many regional gods competing for their affections. Syncretism and Monolatrism were the bane of the prophets’ existence. ‘How long will you waver between two opinions? If Hashem is God, follow him; but if Baal is God, follow him,’declared a frustrated Elijah who wanted the Jewish people to make their mind up. But there is no notion that Hashem had been forgotten about at any point,or that the transmission of g-narratives down the g-chain had ever been threatened. On the contrary, the Biblical critics would have us believe that the various tribal traditions and legends that went into the formation of the Bible stretched back into the very distant past.

The Kuzari Principle had to face off five major concerns. Having looked at each of these concerns in turn, it looks like aversion of the argument can still survive:

(rKP1) A myth will not initially find any traction with a culture who know it to be historically inaccurate, although once it has been adopted and becomes culturally significant, then a culture will not abandon it merely because of its historical inaccuracies.

(rKP2) The generations of a g-chain will not accept a g-narrative about them unless:

a. The generation is the first in the g-chain and witnessed the events for themselves,or

b. The generation received the g-narrative as an inheritance from their parents,although each generation after the first may have members outside of the core of the g-chain who adopt the g-narrative as they join or merge with the community and adopt its history as their own, or

c. The entire generation becomes convinced, presumably only with a large amount of evidence, that a g-chain that was supposed to have reached them was broken – this doesn’t seem to be the case with the small number of Jewish g-narratives,all of which seem to stretch right back into the mist of Jewish pre-history.

(rKP3) G-narrative scan be subject to slow corruption and exaggeration. Thus, the fact that ag-narrative is widespread among a contemporary generation of a g-chain is no reason to believe that that g-narrative presents an accurate history.

(rKP4) The original g-narrative, before any corruption or exaggeration, must have been sufficiently impressive in and of itself to have initiated a sustained desire to transmit the story down a g-chain.

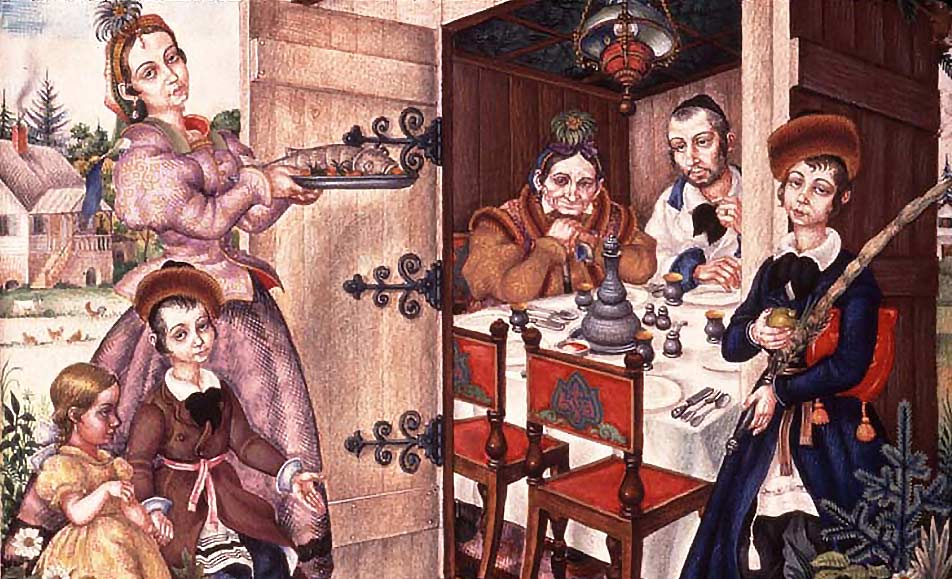

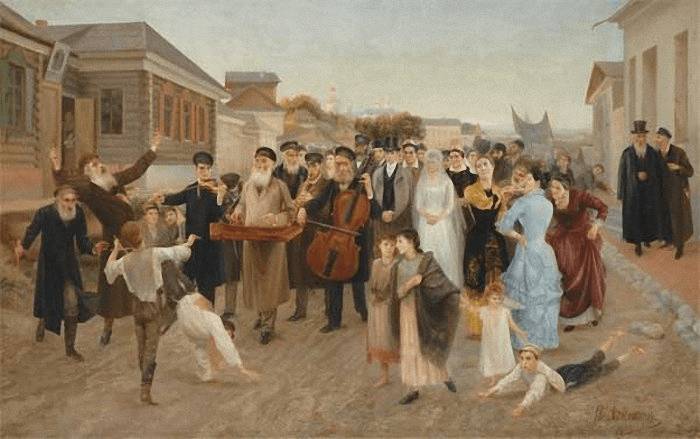

(rKP5) There are a small number of remarkable and widespread g-narratives about the Jewish people, about mass revelation and divine deliverance. These narratives are still transmitted to the majority of Jewish children by their parents at events like the Seder Night, in which Jewish parents recount the exodus from Egypt for the benefit of their children. This ritual retelling is even conducted by a very large number of Jews who no longer believe in the historical accuracy of the narrative.

(rKP6) Given(rKP3), the fact that these g-narratives are widespread among the living members of the Jewish g-chain is no reason to trust the historical accuracy of the stories.

(rKP7) But,given (rKP2) and (rKP4), the fact that these g-narratives are widespread does provide good reason to believe that the story wasn’t initially adopted by a generation to whom the story didn’t actually happen, and that the story is grounded in fact even if it’s been distorted, and that the facts, in and of themselves, were sufficiently impressive to generate the very long lasting feeling of cultural obligation to pass the story on down the g-chain.

(rKP8) We have no reason to believe that the details of Jewish g-narratives are historically accurate, but we do have reason to believe that they are grounded in extraordinary facts witnessed by an entire generation of the g-chain.

(rKP9) Therefore,we have good grounds to believe that an entire generation of the forbears of the Jewish people, or an entire generation of a tribe that would later amalgamate into an emergent Jewish people, were collectively witness to an extraordinary sequence of supernatural events, and events that would have been collectively understood as Divine revelation.

We dismiss (P1) with (rKP1). (P2) is given due weight by (rKP3) and (rKP4). (P3) is duly noted by (rKP2b). (P4) and (P5)really shouldn’t bother us, for reasons I went into above, but the revised argument alludes to them with (rKP2c)

I contend that this revised Kuzari principle makes it rational to believe that the forbears of the Jewish people experienced amass revelation of Divinity and that there was a miraculous Exodus from Egypt,even if the numbers involved were very much smaller than in the Biblical account. I’m interested, as always, to hear people’s responses!

Share This Post

Sam, this is interesting and the analysis of the argument is helpful. I'm still not convinced of its soundness though.

Couple of points:

The King Arthur counterexample is a good one, and I don't think KP*4 does the work necessary to defeat it.

KP*4 assumes that points G1 and G2 are true, but also that the tribe came to believe G1 and G2 at the same time.

What if a tribe somehow started believing a G1-type claim like Arthur, which as we've seen can happen (some Greek myths might also qualify)? Every generation receives this tradition from their fore-bearers. At some point, people come to believe that the act of passing on the story is a part of the story itself. Maybe it's not explicitly stated, but the way the story is told makes it seem that the telling itself is significant. At this point, the tribe would start believing G2 but wouldn't run into the sorts of problems that are entailed by G2 being in the picture at the time that the story first came to be believed.

This seems like a quibble, and it is. I suspect that with a bit of time I could find a couple more, though you might be able to fix them. But actually I'm a little distrustful of the project as a whole here, applying analytical tools to the argument. The Kuzari principle's flaw is it tries to apply logic to an array of highly complex sociological phenomena. We don't really understand things like cultural memory and the development of mythos. We don't really understand how ancient Israelites saw the world. I'm not sure analytical tools can do very much work here at all.

Thanks Arieh, you point about the time at which G1 and G2 are accepted is a facinating one. I have fleeting feelings that its deeply relevant and potentially destructive to the argument, but then fleeting feelings that it can be overcome, or that its not as bad as it sounds.

Either way, it's a good point and I need to think about it.

I don't think there's anything inherently wrong with applying logic or analysis to this general topic, but your last paragraph still gets right to the heart of the matter. (rKP1)simply assumes too much about the processes by which myth was adopted in ancient cultures. This doesn't mean that the argument isn't sound, but that it hasn't yet proven to be sound. That is to say, we need more data. We need to know from ancient historians and anthropologists and the like, a lot more about these topics. But if we found out that (rKP1) and (rKP2) were true, then the argument would have a lot of force, or so it seems to me.

Finally, its worth noting, that the argument never sought to prove beyond any doubt that certain historical events occured; it rather seeks to provide epistemic warrant for a certain set of beliefs about the past. So, the argument isn't as ambitious as some people make out.

As always, thanks for your thought provoking arguments (and if I ever publish anything on this, I'll attribute the King Arthur example to you!!).

Shabbat Shalom

I've had a little think about your first point. Now I know why I both agreed and disagreed with it!!

It seems to me that, on the one hand, you're right. Conceivabley, G2 might only become a proper part of the story many years later, which would cover up a potential gap in the transmission of the story.

But, for any given G-narrative, that would be an empirical question – what sort of gap was there between the adoption of G1 and G2? And, how can we know, even if there *was* a gap, that the transmission of the core narrative nevertheless stretches so far back in time that it could only have been adopted by a people who knew that it was true.

Even according to the Biblical Critics, the story of the exodus (at least the G1 part) was known to the tribe/tribes that the story was about, already in the pre-history of the Jewish people.

This again increases the likelihood (because increasing liklihood is all that kuzari principle is good for) that the story streches back as a cultural narrative, pretty much all the way back until it was alleged to have happened; making its initial adoption unlikely, unless the story was true (albeit the story before it was exagerrated and corrupted over the generations), even if G2 was, itslef, a later addition to the story.

I'm not being very eloquent here. Do you get my point?

So, once again, we come back to you last point: we need to know a lot more about ancient Israelite culture and the birth of mythology in general. Notwithstanding all that you say, the Kuzari argument certainly could prove its conclusion – that we have epistemic warrant to believe in some sort of Divine interaction between the forbears of the Jews and God. All we need to know is how far back in time people were telling G1. G2 is simply a way of making sure that the narrative stretches all the way back. But if G2 is found to be a later addition to the narrative, the argument can still work, as long as we have evidence that G1, by itself, streches far back enough in time, as a traditional narrative, to ensure that its origional tellers had to have known whether or not the story was true.

Does this make sense?

I think Arieh’s question is pertinant and you do nothing to answer it. In your very hypothosis you conceed that the whole theory can only work for a “g-narrative”, but you never state that a normal myth can not change into a g-narrative at any given point. As such if the principal does not wrok for a normal myth it can not work fo a g-narrative either as all a g-narrative is is a morphed myth.

“But, for any given G-narrative, that would be an empirical question – what sort of gap was there between the adoption of G1 and G2?”

Only makes any sense at all if you *know* that the time gap between the two was very small indeed. Once you have the potential for even a few generations between the “event” and the “G1” and similarly between the “G1” and the “G2” that would surely be more than enough time for the whole myth to evolve.

Thanks for this Yoni. Yes, I accept that the theory will only work if there is some reason to think that a normal myth can’t morph over time (or at least not over too much time) into a G-narrative.

I do have reason to believe this to be true, and if I ever publish anything on this topic, I’ll take your point into consideration. Thank you.

I'm not sure the first part of (rKP1) is acceptable. Can it be rephrased, as in "A myth will initially find traction within a culture that thinks it to be historically accurate"?

Now the issues are clearer. What is the basis for determining why myths do or do not gain traction in a culture? The answer–whatever it is–comes from historical studies and interpretations of data. The answer is not one that comes very well from philosophy, or at least philosophy alone.

My whole series of Kuzari posts comes back to this basic fact, that no "principle" itself carries much weight in helping to answer historical questions. As I have asked with respect to the alleged revelation at Sinai, "if we have no evidence today of the single most extraordinary thing that's ever happened in the history of the universe, how much credence is appropriate for me to give?"

Larry,

Thank you so much for the comment.

Yes, I can accept the amendment to (rKP1) though I'm not convinced that it's totally necessary.

The basic fact that you say you keep coming back to is certainly not in dispute by me. I agree: No principle itself carries much weight in helping to answer historical questions.

In many areas of philosophy, the philosopher has to wait to see what other disciplines discover. Think for instance of the effect that Einstein's theories about space and time have had over metaphysics. Philosophy has to be in conversation with other disciplines.

I am convinced that (rKP1) could only be made plausible by a great deal of historical and anthropological data and educated interpretation of that data.

All of that being said, I'm merely interested to find out the following from you:

1) Do you accept that my reformulation of the Kuzari argument (let's call it that, instead of the Kuzari principle), is better than other formulations? Better in terms of having fewer obvious holes and flaws, and in terms of being more persuasive, even if it doesn't actually convince you.

2) Do you accept that if all of the premises of the argument, as I have reformulated them, were shown to true (with the help of historians and anthropologists), then you'd actually have good reason to believe that something like the revelation at Sinai happened even though we don't have any 'direct' evidence of it?

As far as I'm concerned, that is the only power that the Kuzari argument could possibly hope for: the power to justify our belief in Sinai, or something like Sinai, without direct historical evidence. But you'd still need something like 'indirect' historical evidence; i.e., evidence about how myths were formed in ancient times. I'm not claiming that we can arrive at justified historical beliefs a priori.

I look forward to continued discussion with you, and to your answers to these questions. I'm certainly far from convinced that the Kuzari argument is even as strong as I suggested in this post. So, the discussion is really important to me. Best wishes.

Thank heavens I found this!

I've been looking for a more rigourous analysis of the Kuzari argument for months now!

Also going to take this material for a seminar I'm running for hineni.

Can you check out my blog and tell me what you think of the video in my first topic?

Yechonan, can you post the url?

I am not a biblical scholar but I would like to point out what I see as a flaw in the Kuzari argument.

This argument is based on

a) a whole generation of people witnessed an event

b) there was an uninterrupted chain of transmission.

How do you explain the widespread belief that Jesus rose from the dead ?

One could say there was an uninterrupted chain of transmission here as well.

Either way I think the argument falls apart because you cannot prove that the events occurred as written. We have no way to prove how many people did or did not witness the events despite the claims for uninterrupted transmission.

For a total different explanation: http://torahleadership.org/categories/kuzariaudio.mp3.

Sam,

Firstly, I appreciated my contribution to this post is somewhat late, but I have only just come across this blog.

What strikes me as a common feature of many of your posts, is the concession that, whilst the main feature of the stories in the Torah are historically accurate, viz. the exodus of a tribe or the giving of the 10 Commandments, the narrative we find in the Torah is not historically true, but rather true in terms of its philosophical and (more importantly) moral lessons. This has two potential problems in my opinion:

1)Surely what underpins the great deal of value that Orthodox Jews place on the Torah is that each sentence has theological worth in that it is inspired by HaShem – indeed that is the justification of all exegesis and Halakha. However, if many of the aspects of the stories are human fabrication (presumable this would include certain details of the event and laws we derive from them), where is the religious justification to follow them?

I notice you make a very interesting and (in my opinion) correct observation in terms of internalising HaShem, making him more than just a propositional truth, by way of following the laws laid out in the Torah. But if these laws are retrospectively contrived by man – in order to convey a moral message – then, although they may be deeply meaningful narratives, there appears to me to be no real theological justification for following them.

2)The Jewish belief in HaShem hinges on the account of our personal experience of HaShem when giving us the Torah. Now, if we are to say that the story if revelation in Exodus is just (I say “just” but it probably isn’t an appropriate usage) a human construct – rooted in a small amount of (unproven) historical truth – then is it now not open for someone to make the following claim:

“The belief in HaShem is rooted in the Torah. But the Torah is full of human concoctions. Could HaShem, then, be another human concoction used as a literary tool to give foundations to the moral teachings found in the Torah?”

Indeed, you say yourself (unless I have misread you), that if we make-believe notions concerning HaShem, then these notions hold greater influence for us because they become more than mere propositions. So too, could the author of the Torah not make-believe HaShem, in order to provide more practical strength to the author’s teachings?

I am not saying I believe what I have just written, but it would be interesting to have your opinion.

Thank you Dominic for your comment and for engaging in my work.

First: a disclaimer… much of what I post up here is a work in progress and my views on a lot of this are in flux.

In response to your first point:

I don’t actually deny that each sentence of the Torah has theological worth (although I’m not sure what that means, I guess you mean something like very deep significance). And, nowhere do I say that the stories are human fabrications.

So I hope that that clarification helps to remove some of the urgency of your first question. But to clear up the confusion, I can state the things that I do think, that may have lead you to read me in the way you did.

i) I do think that there was some sort of revelatory event at Sinai, although I’m agnostic as to what exactly its content was

ii) I do think that, even if Hashem wrote every single work of the Pentateuch and handed it to Moses, it doesn’t mean that the stories contained in the Pentateuch happened, as they are reported to have happened. Why? Because God didn’t necessarily write a history book. He wrote a Torah; whatever that is.

iii) I do think that even if you don’t believe that certain ‘historical events’ reported in the Torah happened, you should still make-believe that they did.

iv) I think that, because God was involved with the inception of our religion in Sinai, we have reason to believe that he wants us to engage with it, even as it evolves and changes over time.

v) Given (iv), I think that even if the Pentateuch had been written by human beings (a claim that I don’t make, but let’s accept it for the sake of argument), you might still have reason to make-believe that God wrote every single word, since Jewish tradition, as it has evolved, makes that claim, and we have reason to believe that God wants us to engage with the claim

vi) If you have reason to believe that God actually wants you to treat the Pentateuch as word for word and letter for letter, his creation, and if you have reason to believe that God wants you to respect the halakhic system as it has developed over the years, I now think that you have ample reason to commit Orthodox Judaism, even without belief that God wrote the Torah word for word (although I’m happy to believe that he did), and even without belief that the historical narratives of the Torah actually occurred as described.

Does that help to clarify the position, and to answer your first question?

In response to your second question:

Yes. I think it is theoretically open to the non-believer to think of God as a human construct. And, I think that our best reasons for disagreeing are bound up with religious experience and the sensus divinitatus.

Warm regards and thanks again.

Hi Sam,

Thanks for answering my questions. Just a quick follow-up one, though. Perhaps it’s a poor question but, what reasons do you have for thinking that: “God was involved with the inception of our religion in Sinai”?

I think there may be two possible answers here. 1) that it is simply what is stated in the Torah and the Torah is divinely inspired by God. But there is obvious circularity here, so I don’t like this answer. 2) it validates (strengthens, gives meaning to, etc.) orthodox practice, so whilst I don’t really believe it to be the case, it another make-belief in itself worth keeping.

I prefer 2), but also feel in inadequate. I don’t think 2) rules out any belief in God, it would just make God an unknowable being and halakha the Jewish way of relating to God or living a God-orientated life. But this response is inadequate for me mainly because it leaves open the claim that: “for the ancient Israelite’s/Rabbis, mitzvahs/halkhha is the way they related to God, but we in the 21st century feel eating pig (a stupid example) is the best way to live a religious life”. I see no way of holding 2) and being able to give a good response to this claim. But, perhaps you can?

Or more likely, you may have a 3rd and better option (that you yourself hold), so I would be interested to know what it was.

I hope this is clear?

Hi Dominic,

I agree that your option (1) would be circular.

Option (2) might work for some people, but it doesn’t work for you, and it doesn’t work for me.

I think my option (3) would be based upon some revision of the Kuzari argument (hence the post above) that doesn’t bring us a heavyweight conclusion that the Pentateuch was word-for-word authored by God, but might deliver for us the conclusion that it is probable that some unprecedented religious experience occurred for some mass of our ancestors at the dawn of our religion. Once you believe that that is probable, and once you’re convinced that the Jewish religion is a great vehicle for continued religious experience in your own life, I think you might have warrant to believe that some sort of revelatory event occurred at Sinai.

This is just a sketch, and I’m really not as sure as I was, when I wrote this post, which wasn’t all that sure in the first place!

To be sure, “the Kuzari Principle” is a 20th century invention, and far from R’ Yehudah haLevi’s intent.

In answer to the king’s question about the Rabbi’s “G-d of Abraham” etc… rather than the G-d of creation, the Rabbi answers:

1:13. The Rabbi: That which are describing is religion based on speculation and system, the research of thought, but open to many doubts. Now ask the philosophers, and you will find that they do not agree on one action or one principle, since some doctrines can be established by arguments, which are only partially satisfactory, and still much less capable of being proved.

Or later in par. 63, the Rabbi says: “There is an excuse for the Philosophers. Being Greeks, science and religion did not come to them as inheritances.”

So, a bunch of rabbis focusing on outreach thought that invoking proofs would convince people. Now that Postmodernism is in vogue, that’s not all that true. Even among people who think they consider proofs the surest way of knowing things, when it comes to actually being convinced, we don’t think that way.

Besides, any psychologist would tell you that a decision that we invest in as deeply as religion isn’t going to be objective. In such cases, the mind justifies what the heart already concluded.

What Rabbi Yehudah haLevi does argue in section 1 is that tradition is a more sound justification for knowledge than philosophical proof is. Therefore, he certainly would not be busy trying to give our trust in tradition a philosophical basis!

As another indicator, note that the question as posed is not whether or not there is a G-d, nor whether G-d cares about our actions and poses an absolute moral code. The set-up makes that a given. The whole reason why the king is exploring is because (quoting 1:0):

… He had a dream, and it appeared as if an angel addressed him, saying: ‘Your way of thinking is indeed pleasing to the Creator, but not your way of acting.’ Yet he was so zealous in the performance of the Khazarian religion, that he devoted himself with a perfect heart to the service of the temple and sacrifices. Despite this devotion, the angel came again at night and repeated: ‘Your way of thinking is pleasing to G-d, but not your way of acting.’…

Mica… I completely agree. I can’t remember if I wrote it in this blog (which is from a long time ago now) or elsewhere… but I’m convinced that the Rihal had no intention of formulating an argument of this form – it’s merely an argument that’s been based on his words – that’s all.

In fact, Saadya Gaon comes much closer to advancing something like this as an argument.

I’m convinced that the Kuzari as a book takes the stance that arguments can somehow soften you up, but religious experiences (be they the dreams in the book, or the experience in the cave) is what really undergirds faith and even conversion.

Even so, it’s philosophically worthwhile to take this new-fangled argument, that has been superimposed onto the Kuzari and discuss whether or not it has any merits in its own right.

Micha

Thank you for your comment.

Just to make sure I understand your point correctly, please can you help me out with the following three questions:

1) You write: “Besides, any psychologist would tell you that a decision that we invest in as deeply as religion isn’t going to be objective. In such cases, the mind justifies what the heart already concluded.”

There is an important distinction between what a person believes and what that person ought to believe. The first is of most interest to the psychologist, while the latter to the philosopher. Are you saying that the (normative) philosophical project of epistemology is irrelevant with respect to religious belief?

2) You write: “What Rabbi Yehudah haLevi does argue in section 1 is that tradition is a more sound justification for knowledge than philosophical proof is.” Please can you explain in more detail what you think HaLevi means by this? That is, in what way is tradition a more sound (better??) justification for knowledge than philosophical proof? And, in particular, what does “knowledge” denote in this context?

3) You write: “Now that Postmodernism is in vogue …” Please can you explain what you mean by this?

Thanks,

Dani

1- The question the king asked the rabbi was why he believed, not why he /should/ believe.

But in any case, if we found out that philosophical proof cannot work, because it requires a level of objectivity humans are incapable of, and it requires non-empirical first principles, ie postulates about things other than physical objects, before we even start logical reasoning. In other words, the proof is a huge edifice built upon some set of self-evident givens. But what set of non-physical givens are self-evident?

This is why the Scholastic project was given up on, why philosophy went on to debates between the Realists and Idealists and eventually goes through Kant’s “Copernican Revolution”.

The option of using philosophical proof was taken off the table; it’s not even a possibility in the ideal.

2- I meant knowledge in the classical, Platonic, sense — justified true belief. In other words, if we believe something for good reason and it happens to be true, we can be said to “know” it. (Yes, there are issues with that definition, like the Gettier Problem.)

So, the question is, what a “good reason”. Given what I said above about the problem of picking out postulates or even judging which lines of reasoning is sound, proof is not as strong as a reason as it seems.

To Rihal, trust in one’s tradition is a better justification. In his day, perhaps a majority of the world belonged to Abrahamic Faiths who agreed on these things.

Nowadays, we are more likely to get Existential or neo-Kantian, and rely on our own first-hand experience.

In other words, I don’t keep the halakhos of Shabbos because I have a proof that the world was creator, that the Creator gave us the Torah, that the Torah included the Shabbos and defines a halachic process, etc…. I keep the laws of Shabbos in all their obscure detail (like everything that goes into just making a cup of tea according to halakhah) and find that their salvific effect argues that halakhah is from G-d, and thus argues for Sinai and creation.

3- Post-Modernists not only have a hard time agreeing on non-physical postulates, they confuse that with believing they exist. In post-Modern dialog, people don’t speak of what is true in the metaphysical or moral domains, they speak of what is true *to them*. Because these things can’t be objectively proven, or even can justifications in general be easily shared, the post-modernist confuses the personal nature of a justification with the subjective nature of the conclusion.

As a metaphor: Mathematicians tend to treat the “elegance” or “beauty” of a proof as indication that it’s more likely to be sound. After all, we expect truth to have a certain coherence; that’s what Occam’s Razor is all about.

Beauty is an aesthetic judgment. It’s personal. As they say in Hebrew, “About taste and scent, there is nothing to disagree.” And yet, most people like chocolate. There is something objective about chocolate that makes it likely to be desirable by most humans. Just as there are objective features of a math proof that will produce an overwhelming consensus about its aesthetics.

Or features of Torah.